FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

September 21, 2016

Contact: Tamar Russell Brown, Gallery Sitka — 978.425.6290

Works from Prestigious Collection of 20th Century British Masters to Be Shown in Westford, Curated by Gallery Sitka

SHIRLEY, Mass. — It isn’t often that an art collection serves as a window on an entire era, both in terms of the artwork itself and the lives the artists. Yet works from the Ethel Scott Willans Collection, presented by James A. Normington in an exhibition curated by Gallery Sitka, offers the views of seven perceptive British painters whose life stories and long, fruitful careers cover the 20th century and capture the spirit of the times in which they lived and worked.

“This exhibition is very interesting from a historical perspective,” says Mr. Normington. All but one of the seven — oil painter and watercolorist Elaine Cunningham — are no longer living, and as a result most of their works reflect the joys and anxieties of the last century, not the current one. The seven are linked with other outstanding artists and teachers of their times, but also with some larger-than-life British personalities who cast long and sometimes haunting shadows over the period in which these artists thrived.

The show includes three drawings by Charles McCall of Edinburgh, who studied in the 1930s with acclaimed colorist S.J. Peploe. McCall’s career was chronicled by BBC Scotland in 1975. He died in 1989 as a respected member of the Royal Institute of Oil Painters.

Bill Lowe was an accomplished landscape and seascape painter whose lovely watercolor rendition of “Cayton Bay, Scarborough” appears in the show. His paintings can be found in private and corporate collections all over the world. Mr. Lowe was active with the Fylingdales Group of Artists until his death in 2006.

Rudolph Helmut Sauter was born in Germany in 1895 and became a naturalized British subject at an early age. His acceptance into British society, however, did not prevent the government from clapping him into a prisoner-of-war camp north of London toward the end of the First World War. A noncombatant, Sauter had the bad luck to have a German name during one of the bitterest periods of European history, when tens of thousands of young men were dying each month in battlefields all over the continent. Sauter’s imprisonment prefigured the plight of Japanese-Americans locked up in concentration camps in the United States during the next war. The young artist responded to his ordeal by producing a work in sepia ink wash that was later given the title “Prisoner of War Camp, World War I, Alexandra Palace.” In spite of his difficulties during the war, Sauter had the good fortune to be the nephew of novelist John Galsworthy, and he illustrated a definitive edition of his uncle’s works. The painter later exhibited his work in London, Paris and New York.

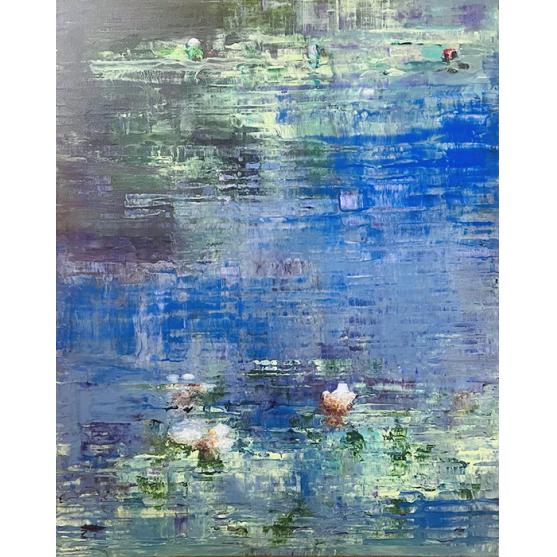

Elaine Cunningham studied at the Duncan of Jordonstone College of Art & Design in Dundee, Scotland. She has shown her work extensively in Ireland, Scotland, England and Switzerland, and her paintings grace public and private collections in both Europe and the United States. “I have lived most of my life near the sea,” says Ms. Cunningham. “It is very close to my heart and is a constant influence on my painting.” Her seascapes are dramatically windswept and dark. She utilizes a wide range of materials, including oil paint, charcoal and watercolor. Her “Grey Day, Arbroath” is an oil painting selected for the show.

Imagine the inconvenience of having five first names. “That’s a common problem for members of the British aristocracy,” says Mr. Normington, and George Alexander Eugene Douglas “Dawyck” Haig, the Second Earl Haig, is no exception. He signed his paintings simply “Haig,” and was known to friends as Dawyck Haig, preferring to go by that ancient Norse name rather than his four Anglo-Saxon appellations.

Haig carried a much heavier burden throughout his long life: being the son of a man much despised in some quarters in Britain. Douglas Haig, the First Earl Haig, was the commander of the British Expeditionary Force in World War I, and earned eternal fame (or infamy) by sending more of His Majesty’s soldiers to their deaths than any other military figure in British history, at the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Military historian B.H. Liddell Hart wrote that the Field Marshall was “a man of supreme egoism and utter lack of scruple — who, to his overweening ambition, sacrificed hundreds of thousands of men…who gained his ends by trickery of a kind that was not merely immoral but criminal.” Such judgments are not universal but were common enough during the painter’s lifetime, and Dawyck Haig must have been torn between loyalty to his father and a strong desire to escape the gloom and tragedy that would always hang over his life and family name.

According to his obituary in The Guardian, Haig spoke late in life about having to deal with the grim legacy of the Great War when he was just a boy. “I remember seeing all those men in hospital, limbless or on crutches. It was harrowing …”

Young Haig served in a unit known as the Royal Scots Greys during World War II, ending up in a German prison camp near the town of Colditz, where he relieved his boredom by drawing. Toward the end of the war, the camp commandant learned of his famous prisoner’s expertise as an artist and sought his help in trying to rescue a nearby private collection of paintings by transporting them to the west, apparently preferring that the British, the French or the Americans got the artwork instead of the advancing Russians. But Haig “didn’t think the paintings were worthy of saving,” according to Mr. Normington.

After the war, Haig had his first exhibition in London at the Redfern Gallery in 1949. In 1956 he sold a portrait at Christie’s that insured his renown as a painter. His “French Town,” painted in 1951, is Haig’s picture for the upcoming show. Mr. Normington does believe that a certain sadness clings to Haig’s pictures, as an online search of the artwork reveals. The landscapes are strikingly colorful but somehow dark and mournful, and even the portraits have a quality of loneliness about them. The painter died in 2009 at the age of 91.

The show further includes an untitled landscape, an oil on board by Frank P. Kirk. The show also features another untitled work, a drawing by Sir William MacTaggart. Sir William studied at the Edinburgh College of Art. He first exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy of Art in 1921. He had shows at the Connels and T&R Annan and Sons, Glasgow, as well as at Aitken Dott, Edinburgh and Stone Gallery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and many other public and private galleries. His work can be found in many collections in Britain and overseas.

Mr. Normington is proud of the Collection and even more proud of its founder, his great-aunt Ethel Scott Willans. “She inspired many people,” says Mr. Normington. She was an enthusiastic patron of the arts and was herself a painter, as well as a violinist and a singer. She and her husband Henry Scott “were polymaths who travelled widely and each spoke several languages,” Mr. Normington informs us. She died in 2001.

This event will take place at the Edward Jones Office of James A. Normington, 225-A Groton Road, Westford, Mass., on Wednesday, Sept. 28, 5:30 – 7:30 p.m. Refreshments will be served. Proceeds from the exhibition will benefit the scholarship fund of the University of St. Andrews, Fife, Scotland.

For more information about the exhibit and the Ethel Scott Willans Collection, contact Tamar Russell Brown, Gallery Sitka, at tamar@gallerysitka.com or at 978.425.6290.